Effective succession planning can help organizations maintain continuity, minimize disruption during leadership transitions and ensure a pipeline of skilled employees for crucial roles. However, as of 2021, a mere 34% of participants in PwC’s US Family Business Survey 2023 confirmed the existence of a comprehensive, well-documented and effectively communicated succession plan for their businesses.

Communication, leadership development and transition timelines were among the many topics discussed recently during a panel moderated by Beth Collins, vice president of sales at the Kansas City Business Journal. Several area leaders shared tips, insights and strategies to help managers and owners achieve the future they envision for their employees and businesses.

BETH COLLINS OF KCBJ: How early should a company consider discussing succession planning or transition? And who should be included in that discussion.

ADRIAN NOHR OF CLA: My advice to clients is that it’s really never too early. We’re often helping people that may be 10 years out.

In that decision-making process, you want to include the people you trust the most in your life, such as family or management team members. I also recommend that my clients have those trusted legal, accounting and tax advisors lined up who specialize in transition, even if that transition isn’t expected to take place for many years.

GREG TREES OF DIALECTIC ENGINEERING: At Dialectic, I started our transition planning as the CFO when our CEO said he was going to retire in five years. That’s when we started investigating how to do that.

Our CEO was an engineer who was involved in the business as well as production. We knew we had to start weaning him from production. We started reassigning his responsibilities to other members of the team.

I was looking for his replacement. We weren’t sure if there was anybody internally who could be promoted to fill that position. So I hired a professional HR person to stealthily interview the entire management team. We didn’t want anybody to know the CEO was leaving. So she came in as a consultant to the whole management team, and she interviewed everybody for the job without them knowing it.

By the time our CEO was ready to leave, he had zero responsibilities. Then our plan was that the new CEO could come in and take on the responsibilities they wanted from subordinates, depending on their strengths and weaknesses.

As far as timing, I’d say the minimum is a year, but that’s a stretch. I thought five years was perfect, but 10 years would be magical.

DR. KATIE ERVIN OF CATALYST DEVELOPMENT: We should always be having succession planning conversations with all of our employees, not just executives. What are our team members’ individual goals? Understanding where they might want to move adds great value.

We have to have that pipeline. If we don’t know what people’s ambitions are or how they want to grow, where are we going to be in five or 10 years?

Having those conversations with your people about their growth and where they want to head is really important.

COLLINS: How do we create the career paths to get employees ready to lead?

ERVIN: We can’t assume that everybody wants to move up. We also can’t assume that everybody is a good people leader. You may be a phenomenal engineer, but you’re not necessarily the perfect CEO.

In higher education, for example, we often take good faculty members and move them to a leadership role or promote them to president of the university. If you don’t have leadership skills, if you don’t have the people skills, if you’re not willing to do that work, that’s not a good transition for you.

It’s important as we talk to people about their careers to find out what they want to do and then find ways to expand their influence. Not everyone’s made to be a people leader. And everyone’s motivation to work is different.

TREES: That’s true. But when I went from CFO to CEO here, a lot of people were like. “What? He’s not an engineer. How can he run this company?”

And then I told them I had been running the company for the past three years. People didn’t have insights that the outgoing CEO’s involvement had been limited.

You don’t see surgeons running hospitals. You don’t see the Hall of Fame pitcher running a baseball team. These roles require different skills.

I remember the first time I got promoted and had to manage my peers. I was scared to death. It’s OK to be scared. We’re going to teach you. We need to teach you how to have the conversations with your subordinates in an engaging and positive way and still get them to do their job.

It’s important that you have the tools. I often hire consultants and coaches to sit down and go through role-playing. People need to role-play so that when they actually do get the opportunity to do these kinds of things in their new job, they’re not doing it for the first time. They’ve actually practiced it and had guidance.

ERVIN: There’s a great book called Who Says Elephants Can’t Dance? by Lou Gerstner about IBM being on the brink of closing. They hired Lou Gerstner, who was the former CEO of RJR Nabisco, and people said, “How can you run IBM? You don’t know anything about computers.” He responded that he didn’t need to know about computers. Instead, he said he needed to know how to get the right people in the right seats and then support them and trust them to do their jobs.

Often, we try to promote people because they’re good at their current job. We don’t look at their growth mindset or whether we can train them and support them to move into that next role.

TREES: I had to go through all those experiences myself, and that’s how I got to where I am. Katie’s 100% right. I wish I had more help than I did. I made a lot of mistakes. I had to learn the hard way.

ERVIN: That’s why my doctoral research is about workplace motivation and employee satisfaction. So often, we put people in positions without giving them training and support, and then we get mad at them when they fail.

The sooner we can start talking about growth and succession planning and where people want to go, the more tools we can give them to make that transition smooth for everybody.

COLLINS: Adrian, can you talk about what some of those succession options could be?

NOHR: Transitioning to either the next generation or a management team is one option. There are many complex situations to consider when transferring it to the next generation or management team: Do I have the right people identified to step into those shoes? What are the tax implications? Can I gift it? Is it a trust?

Liquidating also is always an option.

An employee stock ownership plan (ESOP) is a great option and a way to reward employees. ESOPs come with some tax benefits. Other considerations with ESOPs include valuation and financing.

The last two options could be selling to either a private equity firm or a strategic buyer. And again, there are a lot of things to consider. Private equity sometimes gets a bad rap, but a lot of the private equity groups nowadays are partnering with management teams to help build them for that next growth phase. So that could be a great option.

Strategic buyers can also bring a lot to the table from a valuation perspective and a payout perspective, and they may have a built-in management team to step in and run the company.

COLLINS: Should you transition all at once or over time?

NOHR: That’s going to depend on several individual factors. From a tax profile perspective, you’d want to consider if the sale is hitting all at once or in installments. A lot of complex situations could impact each owner individually.

TREES: So with the Barkley & Evergreen transition, employees purchased 49% of the shares from Bill Fromm. We negotiated the other 51%. We pre-negotiated a price at seven years out to pull the trigger to buy the next 51%.

Bill stayed in charge of the company because he had a personal guarantee on the 49%. We had to hold him in place because he wasn’t going to let us take his baby away from him while under a personal guarantee.

But once we pulled the trigger on the 51%, the personal guarantee went away and then Bill stepped down.

We had that whole period of time to transition over into the new company, to the new leader, Scott Aylward, who at the time was the number two person in the company.

COLLINS: If you decide to sell, what are some of the pain points and considerations?

NOHR: The main pain points are time and money — investing that time to prepare for the sale process and what buyers are most interested in.

You have to invest in the financial reporting structure of your business and make sure that it is sound. For example, maybe you run a sell-side diligence process. All of this takes time and money and attention away from your business. You need to be considerate and careful when diving into that.

I’ve also found that when the management team is involved in that decision-making process — not just the owner running the show — the transition goes much smoother. I always recommend including management in those decisions.

COLLINS: Greg, Dialectic is a 100% employee-owned mechanical, electrical and plumbing engineering firm. Why would a company choose the ESOP option?

TREES: The ESOP is a great tool if you love your employees and want them to have a good transition. You’re thankful for what they did for you and how they helped you succeed.

There are some tax incentives if you choose to take them. If ownership is spread out over a lot of small owners, they probably won’t take those tax incentives. So that’s not going to be their motivation to sell.

But if you put that coupled in as an owner, you can take a tax-deferred transaction. You get to use some of the funds that you’re getting from selling your company to make you a little bit more money until you actually have to pay taxes on it.

It’s kind of like a 401(k) tax-deferred situation. The owner invests in qualified investments, and then when used later the tax is triggered as regular income. That’s a motivation for the owner.

For most people, the ESOP option is more about the owners not wanting another company to come in. At our company, employees wanted to embrace the ESOP because they felt they could make the company better without bringing anybody else in.

NOHR: To add to that, an ESOP can create an awesome culture. Everybody wins.

There’s a brewery out in Colorado that is an ESOP, for example. They don’t accept tips. They all hang out before and after work. They go rock climbing together. This brewery created a great culture, and you could feel it when you walk in.

Culture these days is so important. That alone is a huge benefit to doing an ESOP.

TREES: If you have a great culture, and you want the company to succeed as your legacy, the sky’s the limit with an ESOP. If employees embrace it and you do it right, they will work really hard and make a great company much greater. You’ll wish you did it sooner.

A lot of owners sell the company and all of a sudden, they watch the company they sold get massive. A Gallup survey from 2022 reported that just 32% of employees are engaged, and the other 68% just phone it in. As an ESOP, I have 80% of my employees engaged because everybody has skin in the game. So obviously I can produce better than my competitors.

ERVIN: You’re absolutely right. According to Gallup, 23% of employees worldwide and 32% of employees in the United States were engaged, and that’s not necessarily actively engaged or highly engaged, it’s just engaged.

Culture is key. Whether you do an ESOP or another type of transition, you have to take care of your people. If you do, profits are going to go up, which means you’re going to have more money in your pocket in the transition. Your company’s not going to be worth as much if you don’t take care of your people.

TREES: The one thing about an ESOP is that it’s not easy. I haven’t seen too many successful ESOPs bringing in an outside leader. There’s usually somebody in the company who gets pushed up to the leadership position.

So if you don’t have that person in place, it’s going to be difficult.

COLLINS: What advice would you give a potential or newly transitioned leader who’s taking over?

ERVIN: Too often, I see new leaders come in and they think they’re the smartest person in the room. They’re going to do this from the top down and only have people in the room who will agree with them.

By using this approach, they’re doing themselves a big disservice.

Don’t surround yourself with people who think you’re the smartest person in the room. You have to be humble. You have to listen. Even if you’ve been a part of that organization, you have to understand that you’re sitting in a different seat now. You have a different lens. It is important to pay attention to that.

Since COVID, we know people’s expectations of work have changed. Dictating from the corner office just doesn’t work anymore.

TREES: I would tell a new leader two things. First, don’t change anything for six months. Forget about everything you think you know. Second, do not blindly listen to your managers. They filter everything. Go to the rank and file. Bring them into the room. Run your ideas by them. Let them poke holes in it.

Managers often are self-motivated for their own careers and will do and say things that may be best for them or what they think the CEO wants to hear but aren’t necessarily best for the company. And your job as CEO is to decide what’s best for the company. So listen to the rank and file. Listen to the managers, and then verify what they’re saying with their subordinates.

ERVIN: If everything is sunshine and roses and cotton candy and unicorns, you need to talk to somebody else. There are problems even in the most wonderful organizations. You have to figure out what those are.

NOHR: The only other piece of advice I would add is, don’t go it alone. I find that those leaders who can build teams are the most successful leaders. So think about who you want supporting you in your new role.

TREES: In addition, don’t put people like you on your management team. Don’t put all Greg Treeses in the same C-suite — you need diversity in thought.

ERVIN: You have to be careful, too, of who you allow to have your voice. People will speak for you and speak your mission forward, and sometimes they have their own agenda in mind.

When a new leader comes in, there likely is jockeying for position. Some people will say and do whatever they can to get a seat at the table.

As a leader, you’re listening and you’re also controlling your message.

COLLINS: What are best practices for communicating a transition in leadership internally and externally?

TREES: With Dialectic’s transition, I first had a meeting with upper management in person. Then I had a meeting with the employees – the whole staff – in person. We had an open forum town hall. Everybody could ask questions. Then we followed up with lots of other communications via email and the intranet about our intentions and what we were going to do.

You don’t want to come in and make a lot of changes, because employees are afraid when there’s a change in leadership. They want to know that you’re listening and that you care. You have to try to eliminate or lessen their anxiety.

With external communications, you have to consider the clients and the marketplace. For some brands a widespread marketing campaign would be sufficient, but we had all of our account directors contact other clients by phone.

Assure clients that this was planned, you have been working on this for years, and nothing is going to change in terms of quality of work we’re delivering. Then follow up with an email more broadly. You might work with five different people at that particular client company. You told the head person, but they’re probably not going to tell all the other people who report to them.

So do an email blast to the client base, letting them know what’s going on. Always be very positive: We’re moving forward. This is an improvement. We’re excited.

Then let the marketing team do what it does best. I have a great marketing team. They knock it out of the park. Let the marketplace know that we’re here and we’re improving. This is a big step forward for us and let’s celebrate this transition of our new leader.

ERVIN: I echo that. Change is hard, and change is scary even if it’s positive change. With any transition, you have to become that chief communication officer. You have to be communicating in different ways, sharing information and making sure your actions are backing up what you’re saying.

I’ve seen transitions go wrong when the new leader comes in and promises to do everything for everyone. It’s a political game at that point because they promised the moon to everybody.

So be careful in communicating where you can, but don’t make promises or overcommit during the transition.

TREES: My first year was pretty bumpy because all of the employees were experiencing a new leader and they got to decide whether I got to work there. And I wasn’t an engineer. So I had a tough first year gaining their confidence that I had my arms around this.

They’re fine now, but you have to communicate.

NOHR: I agree. You definitely want your leaders to know first so that they are not caught off guard, and I imagine they probably already know just by involving them in the process. But make sure that it’s not trickling down before it should. Getting the message out there for everybody else at one time is important.

And there are fun ways to spin it. You can go beyond emails and do videos. As Greg said, make it exciting. Make it a big deal and positive.

No matter what, not everybody is going to be on board on day one. So there’s only so much you can control. But with what you can control, make sure you’re doing the best you can to get the communication out there in the right way.

COLLINS: In addition to the financials and communication, what other steps are important in succession planning?

TREES: The next leader has to be ready. When I approach a company that I want to purchase, I talk to that leader and ask, “Who is your next in command and are they ready?” If they’re not ready, I often end up backing away from the deal.

I tell them to focus on getting that person in play. I tell them I will come back in a year or so, and we’ll look at it again. I will want to hear what they did and how they did it and why they’re ready.

ERVIN: I couldn’t agree with that more. True leadership skills are not something that you just wake up tomorrow and have. Greg, I love how authentic and open you’ve been about the transition, because so often we’re afraid as leaders to admit challenges.

The desire to grow and to get better is so important. If an organization said to you, “Here’s the next leader. Here are the things we’re working on. Here’s our action plan. Here’s how we’re doing it,” I imagine that you may not immediately turn around and buy it. However, you have the confidence that they’re working on what they need to work on.

TREES: Exactly.

NOHR: I will take it even a step further. When I think about the readiness factor, even the person transitioning out needs to be ready. That’s often the business owner.

For many of these business owners, the company is like their baby. We ask them on a scale of 1 to 10, how ready they are for this next phase in their life. Many businesses have been run by the same family for several generations. Before you dedicate the time and money to transitioning, you want to make sure they’re ready.

TREES: The last year before I became CEO, Chris Larson was literally told to be retired but remain informed and on salary as a consultant. He could work on his golf game and be in California the whole year, so I ran the company stealthily. Every Thursday morning I had a meeting with him and I’d tell him what I did that week. If he didn’t like what I did, he had veto power. Then we would redo it or fix it and move forward.

So that was how he transitioned me. It allowed me to make mistakes.

The other thing was he made sure the chain of command stayed intact. There were no end-arounds. For a whole year, people knew they couldn’t go to him first. But if someone didn’t like what I or another manager said, they could still go to him. That’s when he had the opportunity to come back and fix it if he thought we did something wrong.

It really helped the four main leaders figure out how to transition that power slowly and carefully. By the time he was done, we were ready.

ERVIN: I love that process. Adrian talked about the companies being the owners’ babies. The community may also see the company as the owner’s baby. So a well-planned transition instills confidence in other people that when the owner is gone, the company is still going to continue to provide the same level and quality of service.

You want people to know the company is not the owner. So even though the transition may not take place until the end of the year, they are already positioning themselves to make sure people know the company is not the owner who is leaving.

TREES: Katie, many baby boomers are transitioning out of the workforce with a ton of intellectual property in their heads. It’s walking out the door. How do you protect yourself

ERVIN: I love that question. I’m doing a lot of research on generations right now because we have five generations in the workforce these days. Even when you talk about the younger generations, they’re wildly divided. It’s really about how we communicate, how we share information, and how we help transition people.

I’m doing some development consulting with an organization that says it’s their old org against their young guard. That’s not how we want to view it. We all belong. We all want to have a voice. We all want to be included in the conversations.

So the more we get to know each other, the more we connect with each other, the more we understand the generational differences, the more we can actually celebrate the diversity and then download the information.

We still have people in their 80s in the workforce. People are living longer and working longer. We want to include them and celebrate what they know. But it takes intentional work.

One of the things I love to do is get people of all different generations together at the table.

In our programming on leadership development, we have people early in their careers, emerging leaders and senior strategic leaders all sitting at the table having the same conversation.

First, there’s this download and upload of information. Second, it allows us to get to know each other and realize our stories aren’t that different. We’ve walked similar paths. We’re on similar paths and so we can learn from both directions.

TREES: When I first came into the workforce, my bosses told me to work 70 to 80 hours a week. And I did. I didn’t ask questions. I did it and I made a lot of dudes a lot of money.

This generation’s not going to do that. So if anybody who is close to my age, 60, transitioning into leadership thinks they are going to be able to do that, they will fail as a leader. They will absolutely fail. That’s not going to work anymore.

Employees aren’t going to kill themselves for you just because you ask them to. You’re going to have to find other ways to motivate them.

ERVIN: To add to that, we need the grace and understanding to know that people can work at different levels and generate different outputs.

For example, US digital natives, those who grew up in the digital age, can do things in five minutes that may take me a day or two to complete.

We need to focus on whether they are getting the job done rather than on whether they are clocking the time. We can sit in the office 70 hours a week and not get the job done.

That’s where quiet quitting comes in. That’s where that disengagement comes in. We have access to an abundance of things that distract us. So we could sit there and keep the lights on, but are we getting the job done?

I would rather my employees work 30 hours a week and get the job done than sit around with me for 60 hours a week and not get anything done. Flip that mindset to recognize that people are more efficient and effective these days.

COLLINS: How do you support individuals who don’t have the desire to be promoted? And how can we encourage them to grow through this transition process, even if they’re not stepping into a leadership role? The people on the ground have to be able to sustain the company through a transition.

ERVIN: There is great power in people coming in and doing their job. There are people who are keeping the lights on that are plugging along. There’s great power in that. We don’t need a whole organization of hard-driving, overachievers.

We also need to understand that not everyone wants to or can move up. So instead of creating a career ladder, how can we create these paths where people can expand their influence, expand their skills and take on more opportunities?

Often in organizations, in order to get a pay increase or promotion, you have to move up in the organizational chart. Moving up then puts a team underneath you.

So how do we move out and create influence and opportunities?

Again, that’s a mindset flip to say we’re going to give you more influence as opposed to moving you up. I’ve seen some organizations do this really well.

I also recommend providing not only career ladders, but also jungle gyms. Create crossover points. We need to realize that not everyone wants to move up in technical skills. Maybe they want to move over to sales or other customer-facing positions.

Where are those crossover points in the succession planning or in career paths where people can transition to other spots? Not everyone wants to do the same job for 45 to 50 years.

NOHR: In most traditional accounting firms, it’s up or out — you either move up or you’re out. We didn’t want that to keep happening because we lost such great talent.

So we’ve created different roles for different career paths. Maybe it is a lateral move and not necessarily up.

As Katie said earlier, not everybody is good at leading people. You have to create other opportunities to keep the talented people who do not want to oversee a team.

This has been wildly successful from an attrition standpoint.

COLLINS: Before we close, are there any tips you would like to share concerning succession planning or transitioning the ownership of companies?

TREES: Get a good executive coach because you need someone who is going to tell you what your weaknesses are and is willing to tell you what you don’t want to hear.

ERVIN: It could also be an advisory committee. I have an advisory committee. I always tell people, stop being nice and be kind. Tell people the truth and help them grow. It’s so important.

To reiterate Greg’s earlier point, don’t surround yourself with people who look like you and think like you. We have to think about access. We have to think about opportunity.

In Kansas City, while there are some skills gaps, there are some grace gaps, too. We can’t just hide and always hire the guys you love to play golf with. We need to surround ourselves with people who are going to bring different viewpoints.

We need to give people opportunities and grace to grow in careers. I’m not only talking about race and gender, but also socioeconomic backgrounds and age. We need to surround ourselves with people who are going to expand our thinking. When we have more diversity and more belonging in our organizations, profits drastically increase.

TREES: I agree 100%. Bring a diverse range of people into your company — people from other professional, socioeconomic and educational backgrounds, to name a few.

They will bring their culture and experiences with them. They come up with great ideas because they are seeing what we’ve been doing for 100 years for the first time and asking why we are doing things the way we are. It’s great to have that fresh perspective.

COLLINS: Adrian, anything to add?

NOHR: If you are that person who is thinking about transitioning, make sure you have your story of where you’ve been and where you want to go. If you can get that understanding for yourself, you will be able to head in the right direction.

ERVIN: That’s a great point. And take care of yourself through the transition. Not being there all day, every day, is going to be different. Prepare for that and support your well-being.

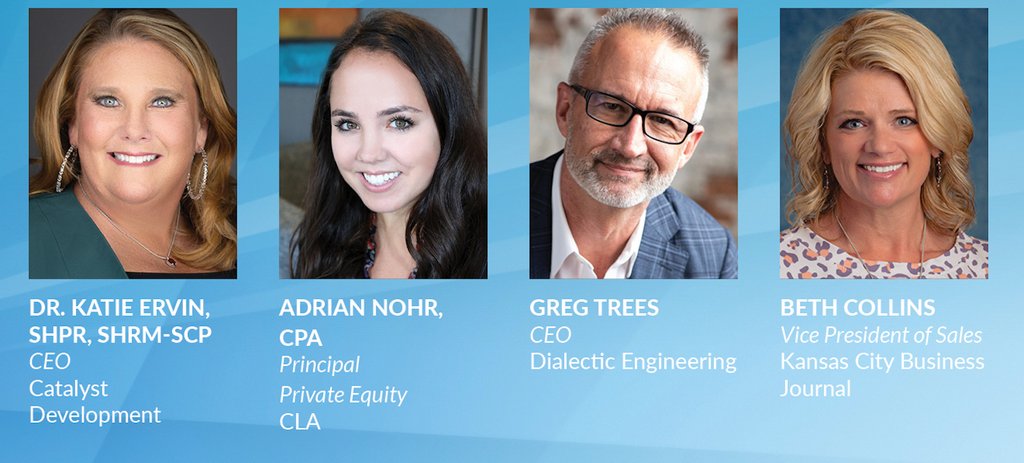

Panelists

Dr. Katie Ervin, SHPR, SHRM-SCP, CEO, Catalyst Development. Dr. Ervin is the CEO of Catalyst Development. In her work, she has saved organizations millions of dollars by focusing on building a strong culture and teaching them to invest in their people. Dr. Ervin’s specialty is developing strong leaders, as evidenced by her catchphrase, “It’s all about the people!” Her methodology focuses on critical career skill-building to develop strong culture and raise profits. Her first book, “You Might Be an A$$hole but It Might Not Be Your Fault,” was released April 21, 2023, and became a No. 1 Amazon new release.

Adrian Nohr, CPA, principal, Private Equity, CLA. Adrian Nohr is a deal services principal with CLA who brings over a decade of experience in working with privately held companies and private equity firms. With a focus on the manufacturing, professional services, retail, construction and technology industries, Adrian has a deep understanding of the unique challenges these sectors face. Adrian’s exceptional knowledge of deal services is completed by her significant experience in owner succession, quality of earnings and post-merger integration projects.

Greg Trees, CEO, Dialectic Engineering. Greg Trees is a seasoned executive and skilled strategic thinker who has helmed employee-owned Dialectic Engineering since 2020, after serving as the company’s CFO. Under Trees’ leadership, the mechanical, electrical and plumbing engineering company’s ESOP has grown 175 percent. He is passionate about teaching teams how to drive toward the top with bottom line success. Trees was named one of Kansas City Business Journal’s Twenty to Know in 2021 and was honored as a CFO of the Year in 2013.

Moderator

Beth Collins, vice president of sales, Kansas City Business Journal. Beth Collins thrives on growth and results. As the advertising sales director, she leads KCBJ’s talented team and oversees business-generated marketing campaigns for its valued partners. Collins has 16 years of experience as a top producer and manager with consultative selling and coaching skills. Her background includes cable, digital and print media sales. She is a member of the Greater KC Chamber of Commerce Centurions Class of 2023.